Santa Barbara – Western Traditions

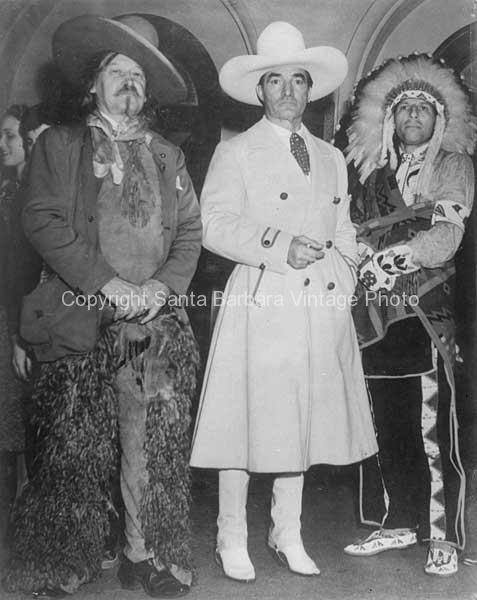

Not too long ago, Santa Barbara was a remote outpost, far beyond the borders of the United States. Cowboys, Ranchers and Vaqueros made up the population of our Western town. Today Santa Barbara proudly displays this tradition in the Carriage and Western Art Museum, located in Pershing Park near the waterfront in Santa Barbara, CA. Established in 1974, the Carriage and Western Art Museum of Santa Barbara is a non-profit organization with the mission to collect, display and preserve historic horse-drawn vehicles, saddles, and western memorabilia.

Some history of western traditions in Santa Barbara… The era that is highlighted during our community’s “Old Spanish Days” Fiesta is commonly called “the Rancho Period.” This period lasted roughly 40 years, taking place from around 1824 to 1864, when Santa Barbara was under Mexican rule and American rule … but not Spanish.

This Rancho Period was a distinct culture. It was neither Spanish nor Mexican, and in fact the people here did not identify as either Mexican or Spanish, but insisted on being called Californios. Furthermore, they had a whole cultural body of work — songs and dances — unique to just California.

Most fascinating was that there were no towns, no stores, no hospitals, and no banks at this time. The people — considered to be among the most outstanding horsemen in history — lived on enormous ranchos of some 4,000 to 40,000 acres, isolated by miles of chaparral. They raised cattle for its tallow and hides utilizing only a barter system, trading with merchant ships from Boston and Europe.

There were neither hotels nor inns, so visitors passing through had to depend on the hospitality of these Californios who graciously opened up their homes, saying, “¡Mi casa es su casa!” — “Welcome, friend, my house is yours!” These hosts then would invite neighboring ranches for a party to celebrate this unexpected arrival of a stranger. Thus visitors were a welcomed presence — they provided an excuse to hold a community party and they brought news of the outside world to isolated Californios.

During this period, Mexico threw out the Spaniards, and closed down the missions. So those Chumash who had lived at the missions for years (and in many cases, for generations) came to work on these ranchos as cooks, weavers, domestics, carpenters, farmers, and — something rarely recognized — the Chumash worked as our earliest vaqueros!

California became a state in 1850 and soon became flooded with Yankees and even Europeans. The heretofore quiet landscape was now filled with new people and foreign languages and commotion. Adobes were exchanged for modern wooden houses, metal carriages replaced the wooden oxen carreta, the renowned De la Guerra home found itself in the midst of a bustling little American town of shops, banks, and hotels. The gentle strum of a guitar could no longer be heard over Professor McCoy’s dashing dance band.

While it was an exciting new era, longtime residents of Santa Barbara would reminisce about the earlier, quiet time before the arrival of the Americans dominating the scene en masse. They remembered how “everyone got along” back then — the Spanish, American, Indian, Mexican, and European — and that everybody took care of one another. And everyone spoke Spanish. They recalled the communal gatherings of the ranchos for a fiesta to share music, dance, food, and news. They would wistfully think back on these “old Spanish days” as halcyon days where people were unbelievably generous to one another and hospitable to strangers.

Contact Us

![]()